The Pollinators with Director Peter Nelson - 2022 Holiday Replay (S5, E28)

Peter Nelson is a filmmaker, director and beekeeper. This combination of skills and passions lead to a documentary film about the business and lives of pollinators - both the two legged and six legged kind! The documentary, is currently making...

Peter Nelson is a filmmaker, director and beekeeper. This combination of skills and passions lead to a documentary film about the business and lives of pollinators - both the two legged and six legged kind! The documentary, The Pollinators is currently making its rounds through the film festivals where it has been well received and enjoyed by all audiences.

Peter Nelson is a filmmaker, director and beekeeper. This combination of skills and passions lead to a documentary film about the business and lives of pollinators - both the two legged and six legged kind! The documentary, The Pollinators is currently making its rounds through the film festivals where it has been well received and enjoyed by all audiences.

In this Holiday Replay episode, Peter joins Jeff and Kim to discuss the making of his documentary. Peter discusses his experiences following and filming the beekeepers,  farmers, environmentalists and even world renown chefs as they discuss the importance of the honey bee to agriculture. The film also explores the dangers and struggles the honey bee (and all pollinators) face with the use/overuse and dependency of modern agriculture on herbicides, pesticides and fungicides.

farmers, environmentalists and even world renown chefs as they discuss the importance of the honey bee to agriculture. The film also explores the dangers and struggles the honey bee (and all pollinators) face with the use/overuse and dependency of modern agriculture on herbicides, pesticides and fungicides.

Listen to the episode and learn what you can do to help the pollinators!

We hope you enjoy the episode. Leave comments and questions in the Comments Section of the episode's website.

Thank you for listening!

Websites mention in the podcast:

- The Pollinators: https://www.thepollinators.net

- More about Peter and his work: http://peternelsondp.com

- The Dance of the Honey Bee: https://www.thepollinators.net/dance-of-the-honey-bee

- Dan Barber and Blue Hill Farms: https://www.bluehillfarm.com

- 350.org, a grassroots organization concerned protecting the environment through online campaigns, grassroots organizing, and mass public actions: https://350.org

- Beekeeping Today Podcast on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@beekeepingtodaypodcast

- Honey Bee Obscura: https://www.honeybeeobscura.com

______________

This episode is brought to you by Global Patties!  Global offers a variety of standard and custom patties. Visit them today at http://globalpatties.com and let them know you appreciate them sponsoring this episode!

Global offers a variety of standard and custom patties. Visit them today at http://globalpatties.com and let them know you appreciate them sponsoring this episode!

We welcome Betterbee as sponsor of today's episode. Betterbee’s mission is to support every beekeeper with excellent customer  service, continued education and quality equipment. From their colorful and informative catalog to their support of beekeeper educational activities, including this podcast series, Betterbee truly is Beekeepers Serving Beekeepers. See for yourself at www.betterbee.com

service, continued education and quality equipment. From their colorful and informative catalog to their support of beekeeper educational activities, including this podcast series, Betterbee truly is Beekeepers Serving Beekeepers. See for yourself at www.betterbee.com

Thanks to Strong Microbials for their support of Beekeeping Today![]() Podcast. Find out more about heir line of probiotics in our Season 3, Episode 12 episode and from their website: https://www.strongmicrobials.com

Podcast. Find out more about heir line of probiotics in our Season 3, Episode 12 episode and from their website: https://www.strongmicrobials.com

Thanks for Northern Bee Books for their support. Northern Bee Books is the publisher of bee books available worldwide from their website or from Amazon and bookstores everywhere. They are also the publishers of The Beekeepers Quarterly and Natural Bee Husbandry.

Thanks for Northern Bee Books for their support. Northern Bee Books is the publisher of bee books available worldwide from their website or from Amazon and bookstores everywhere. They are also the publishers of The Beekeepers Quarterly and Natural Bee Husbandry.

_______________

We hope you enjoy this podcast and welcome your questions and comments in the show notes of this episode or: questions@beekeepingtodaypodcast.com

Thanks to Bee Culture, the Magazine of American Beekeeping, for their support of The Beekeeping Today Podcast. Available in print and digital at www.beeculture.com

![]()

Thank you for listening!

Podcast music: Be Strong by Young Presidents; Epilogue by Musicalman; Walking in Paris by Studio Le Bus; A Fresh New Start by Pete Morse; Original guitar background instrumental by Jeff Ott

Beekeeping Today Podcast is an audio production of Growing Planet Media, LLC

S5, E28 – The Pollinators with Director Peter Nelson - 2022 Holiday Replay

[music]

Jeff Ott: Hey, everybody. Merry Christmas and happy holidays. We’re taking this week off and hope you are too, and taking some time to spend with your family and friends. This week, we bring you a holiday replay of one of our favorite episodes from the past hour-interview with writer and director of the movie The Pollinators, Peter Nelson.

This episode was originally released in March of 2019. Its message about protecting all pollinators, and especially honey bees, is as important now as it was then. It is wonderfully photographed by Peter, who is also a beekeeper, and features many beekeepers you may recognize as being one of our guests. Check out The Pollinators on your streaming service of choice this holiday season. Now on to the show.

[music]

Welcome to Beekeeping Today podcast, presented by Bee Culture. Beekeeping Today podcast is your source for beekeeping news, information and entertainment. I’m Jeff Ott.

Kim Flottum: And I’m Kim Flottum.

Global Patties: Hey, Jeff and Kim. Today’s sponsor is Global Patties. They’re a family-operated business that manufactures protein-supplement patties for honeybees. It’s a good time to think about honeybees’ nutrition. Feeding your hives protein-supplement patties will ensure that they produce strong and healthy colonies by increasing brood production and overall honey flow.

Now it’s a great time to consider what type of patty is right for your area and your honeybees. Global offers a variety of standard patties as well as custom patties to meet your needs. No matter where you are, Global is ready to serve you out of their manufacturing plants in Airdrie, Alberta, and in Butte, Montana, or from distribution depots across the continent. Visit them today at www.globalpatties.com.

Jeff: Thanks, Sherry, and thank you Global Patties. You know, each week we get to talk about how much we appreciate our sponsor support and we know you’d rather we get right to talk about beekeeping. However, our great sponsors are critical to help making all of this happen. From the transcripts, the hosting fees, the software, the hardware, the microphones, the subscription, the recorders, they enable each episode. With that, thanks to Bee Culture magazine for continuing their presenting sponsorship of this podcast.

Bee Culture has been a magazine for American beekeeping since 1873. Subscribe to Bee Culture today. Hey, everybody, thanks for joining us. We’re really happy you’re here. Before we get started, just a quick reminder to subscribe or follow Beekeeping Today podcast and give us a five-star rating. It really does help.

Also, we are now adding complete transcripts of each episode on the website after the show notes. Check them out. You can also leave questions and comments online under each show. You can leave a comment, ask a question, reply to a question, our shortcut listeners. Click and leave a comment at the top of the episode’s show notes to join the discussion.

Have you listened to an episode and thought, “That person sounds really interesting and I’d like to know more about them”? Now you can. Each episode links to a guest profile. Each profile has a guest photo, bio, contact information, including Instagram and Twitter details, if they have them. Check it out and finally share the podcast with your beekeeping friends. Email them links or mention it at your next beekeeper meeting.

[music]

StrongMicrobials: Hey, beekeepers. Many times, during the year, honeybees encounter scarcity of floral sources. As good beekeepers, we feed our bees artificial diets of protein and carbohydrates to keep them going during those stressful times. What is missing, though, are key components. The good microbes necessary for a bee to digest the food and convert it into metabolic energy.

Only SuperDFM-Honey Bee, by Strong Microbails, can provide the necessary microbes to optimally convert the artificial diet into energy necessary for improving longevity, reproduction, immunity, and much more. SuperDFM-Honey Bee is an all-natural probiotic supplement for your honeybees. Find it at strongmicrobials.com or at fine bee supply stores everywhere.

The Pollinators - Bret Adee: Beekeepers are like the last to the cowboys you’ve seen in the westerns. We migrate the bees from up in the northern prairies all down here to the Bakersfield area. We keep them in the west side of the valley. When the spring bloom comes, we’ll take the bees and we’ll spread them from the Turlock area down to the southern Bakersfield area. The almond pollination is the biggest pollination event in the US bee industry. It takes almost the entire national bee supply.

[music]

The Pollinators - Dave Hackenberg: A semitruck can hold somewhere around 400 to 450 hives of bees. When you start thinking about this, it takes somewhere in the neighborhood of two million hives of bees in California, say a couple hundred thousand of them are already there, maybe 250,000 of them are already there, so that means the rest of those beehives have to come from someplace else, so there’s a lot of truck loads of bees crisscrossing the United States.

The Pollinators - Dave Hackenberg: Our honeybees get picked up and move almost 22 times a year. A lot of people think that this is one of the reasons why our bees do not survive like they used to. We’ve been pollinating fruits and vegetables and nuts since the ‘70s, ‘60s, ‘50s, and we haven’t had this kind of losses.

Jeff: That’s from the movie The Pollinators that we’ll be discussing today with our guest, Peter Nelson.

Kim: That little clip was a good summary of a lot of this movie that people are going to get to see, Jeff. I like the reference to cowboys. I think that’s from following the bloom back about 15 years ago. Bret Adee and then Dave Hackenberg talks about the numbers. Then Dave talks about how often they’re moved. The only thing we didn’t get a little bit of in that clip was comments on the diversity of what we need agriculture to go back to.

There’s a lot of that in the movie, John Lundgren and some of the rest. I’ll tell you what, why don’t we go ahead and get a hold of Peter and take it to the next step?

Jeff: I think that’s a great idea. This is a fun movie and I look forward to talking to Peter.

[music]

Betterbee: Has winter’s chill and weather forced you inside? Did you know that Betterbee offers winter classes you can take from the comfort of your own home? Our classes are taught by doctor David Peck and Eastern Apicultural Society Master Beekeeper Anne Frye. Our classes range from basic courses on essentials of beekeeping all the way up to specifics on planning for the seasons ahead and for your success. Visit betterbee.com/classes to view all of our upcoming learning opportunities.

Jeff: Welcome, Peter, to Beekeeping Today podcast. Kim and I have been looking forward to talking to you for a couple of weeks now ever since we heard about your film The Pollinators.

Peter Nelson: Thanks very much for having me. I’m really delighted to be able to talk to you all about it.

Kim: It’s good to meet you in person, Peter. I watched your film. I think three times I made it through and I could not-- I watched it on my cell phone. I couldn’t put it down.

Peter: That’s awesome.

Kim: An easy way to watch a movie, certainly. Knowing a lot of the people that you work with, it was fascinating to see them in the situations that you were at and are here to talk about. What they do for a living?

Peter: Thanks very much. It’s really nice. I’d knew there’d be a lot of people that you would know here in particular.

Kim: Before we get going, why don’t you tell us a little bit about the projects and why you were interested in doing this film, The Pollinators, and what actually got you started down this road?

Peter: I’ve been a beekeeper for about 30 years, sort of a backyard beekeeper. I have a great interest in honeybees, of course. I have a great interest in food and agriculture and sort of combine all those things into making a film. My day job, if you will, is I’m a cameraman, or a director of photography is a fancy way to put it.

I wanted to put these interests together in a film and I didn’t really feel like there’s some great films about honeybees out there. I really felt like the story that wasn’t told was about these commercial beekeepers and their importance to our food system and our agricultural system. I wanted to connect those dots a little bit. I thought doing a film about it might be the best way for me to do that.

Kim: Cool. It’s a really good job and I really enjoyed watching the show.

Peter: Thank you very much. Really appreciate it.

Kim: I like the way that you tied the beekeeping industry and agriculture. Of course, the two sides of agriculture, you worked with the pesticides side and you worked with the soil health side. My background before bees was farming, so I’ve been aware of that tie. Lots of people haven’t been.

It was good to hear you bring in the people that you did, Jonathan Lundgren, and the rest, to talk about what’s doing. I know his work is getting, I should say, more attention, as it should be. I’m glad that you picked up on that. What did you learn from him other than what we saw on the film.

Peter: He’s a really interesting and passionate guy as you know. I wish I could have spent more time with him just. The great thing about this project was, as I was working on it and making this film, I was learning the whole time, which is one of the great things about working on documentary films. John was really generous with his time and he’s able to connect the dots between agriculture, and bees, and pesticides and varroa in a great way.

What I liked about what he said was his enthusiasm and encouragement for alternative paths. There’s not one way to do it. I’m not trying to lecture anybody about how farming should be done. I’m not a farmer, but I think there are some people out there that are really trying to experiment and do things differently, which are really not new techniques.

They’re doing things differently to try and take agriculture in a different direction and approach it because it’s not really working the way it’s now with the vast monocultures that we have and the simplification of agriculture. You can see why agriculture got simplified, because it’s easier to plant, it’s easier to harvest if you grow one thing, but the downside of that is that it’s not really good for the soil and for the environment and there’s a lot of costs in many aspects that come along with that.

Kim: You certainly have that right, and the other thing that these monocultures actually force beekeepers to do is you’ve seen the vast holding yards before almonds hundreds and hundreds, sometimes thousands of colonies sitting in one field and just disappearing into the mist.

I know beekeepers don’t like having to do that, because when you’ve got thousands of colonies, you’ve got thousands of problems and they’re just spread out evenly over everybody. I’m not going to say unnatural, but it’s certainly not the best of all possible worlds. It would be nice if we could divide that up a lot.

Peter: One of the things that it was really drew me to do this project was the fact that I don’t think people know that this happens. People know that bees are important to agriculture I think to some extent. People know that there are problems with bees, and bees are going through some really tough times now. They don’t know what the specific problems are, but I found so often that people had no idea that these commercial beekeepers move massive amounts of bees around the country.

I think it’s really important to know that these beekeepers are not doing this for their own self-interest. They’re doing it because they’re responding to the changes in agriculture, and they’re used to be that they would get a large percentage of their income from honey production. Now it’s almost opposite from what people have told me, that a lot of these commercial beekeepers are getting more from pollination fees.

Kim: It goes back to, was it about 15 years ago and Doug Whynot did the Following The Bloom book. I think that was probably the beginning of this surge, and he noticed it then. It’s only gotten bigger ever since then and then of course, you throw in varroa and all of the other problems that are going on, it’s a tough way to make a living.

Peter: It’s really hard. One of my takeaways from doing this project was just how hard these beekeepers work, and I have had the opportunity to be around a lot of hardworking people in my time working on all kinds of different films. These beekeepers, particularly during the pollination season, almond season, as they’re up all night moving bees gets a little bit of sleep, and then they get up in the next morning, fix the equipment that broke, move things, do the paperwork and trying catch up during the day a little bit, and then it starts all over again.

It impressed me how hard people like David Hackenberg and Bob Harvey, Bret Adee they just work. It just seemed to me like there was no good time to call them, but I could always call them. I’ve always reached them no matter what time of day it was, which is pretty astounding that they can work that hard.

Kim: Cell phones for a commercial beekeeper is your third appendage. They pretty much live on them the whole time they’re moving because that’s the only way to communicate. One of the things that I was also wondering about is your background in beekeeping. You said you’ve been a backyard beekeeper for how many years?

Peter: Just about 30 years. I was that kid that could never be kept inside. I always had a real curiosity about the natural world, and luckily, I had some great teachers in my life that inspired that to learn about birds and learn about insects, and get outside and enjoy the world. That led me almost right into beekeeping and it’s just something that’s always interested in, and so read a bunch of books about it way long time ago and got myself a hive and started up on it and I’ve just never looked back.

It’s endlessly fascinating to me. I’m always finding something I knew that I hadn’t seen before. I tell people jokingly that I’ve been keeping bees for about 30 years and some days I feel like I know a little bit less than when I started. The bees can always keep you pretty humble.

Kim: You have that, exactly. One of the reasons before I knew that you were a beekeeper, I’d watched your movie the first time, and my wife Kathy and I were watching it together and I turned her and I said, “This guy has got to be a beekeeper because he’s looking at things the way beekeepers look at things and it shows up.” It’s really obvious that not only you know do what you’re doing, but you’ve got that curiosity and that interest that a beekeeper’s going to have in this movie. It makes it even more interesting to me.

Peter: Thanks.

Jeff: It’s really spectacular footage that you were able to capture the bees in flight and the high film speed, those was really good.

Peter: Thank you, it’s high compliments from both of you. I really appreciate that. One of my goals was to try and show bees in a way that most people hadn’t seen it before. Using the super high-speed photography was a way that I did that. I did a short film called Dance of the Honeybee several years ago, and it inspired me to work with this very specialized equipment.

I had some great support from a camera company in New York who loved what I had done with their equipment called Abel Cine Tech and their Phantom cameras is the brand name. It was interesting. I really wanted to show people, I think that bees are beautiful. I see them all the time. I’m sure you guys feel the same way, but I really wanted to try and show your average person that these bees are really incredible interesting insects.

The social life of beehives is just fascinating, and looking into that world in a way that I don’t think had been done before was really my goal. I spent a lot of time out in my backyard. I took a part of beehive and cannibalized it so I could shoot in certain ways and I called that Studio Bee.

[laughter]

It was a great opportunity to-- pretty much anytime I had an opportunity, I’d go out and film. What was interesting to me is working in this particular world, and this goes back to my childhood.

If you look down in the grass, in your yard and the clover fields, I would sit down and I could just lay down in my front yard with a camera, which I literally did and found all kinds of interesting insects and was able to capture what would be a normal thing of bee flying in, flying out and try and show it in a way that was almost like a ballet and trying, show it in a way that was really beautiful and extraordinary. I just had the best time doing it, just found it endlessly fascinating.

Jeff: It really shows in the quality of the work that you’ve prepared. Just from a technical standpoint, were you shooting on film stock or is that digital?

Peter: No, it’s all digital. It’s very specialized high-speed cameras. They’re called Phantom cameras and they’re made by Vision products. I think I shot up to 1,500 or 1,550 frames per second was about the fastest I went and keeping it at a very high resolution that I was shooting at in 4K digital.

It was really spectacular to get down there with a macro lens and extension tubes and really try and capture the beauty and wonder of the bees. That’s something that’s actually interesting. Being a beekeeper, there was something that I was able to employ in doing this was an understanding of bee behavior, what was happening, how bees flew, how they landed, how they moved from flower to flower. That was something that I think gave me a little bit of an advantage in capturing the bees in particular in the slow motion.

Jeff: It was really fun. It’s fun to watch.

Kim: You also did a lot of work at night, which had to be tough, not physically tough, but just to get the light right and from where you had to stand so you didn’t get run over and all of those things. That was impressive also. I’ve been there a couple of times I appreciated how hard it must have been to make that work, like I said, without getting run over, and being close enough to be able to show what was going on.

Peter: It was quite an adventure. The bees at night and particularly almonds is crazy. I pretty much had in my mind that would be and I threw that plan out within the first hour of working. The promise that I made to the beekeepers was that “I’m not going to get in the way, I’m not going to get hurt, and I’m not going to interfere with your business.” Other than that, if they’re happy to have me, I’d love to be there.

I really worked hard to try and keep that promise stay out of the way but know what’s going on. It happens fast. I mean, unload a tractor trailer, some of these guys that unload pallets, and the whole thing would be done in about 20 minutes. It was pretty impressive. I found it beautiful because it’s at night, there’s a lot of smoke, there’s no lot of colored lights, and it’s almost like a music video in a way to me.

It’s just a ballet of the bobcats and the hummer bees, zipping around it’s just so much fun, I really had a great time doing it. One of the other things that was really interesting about what happened was that the unpredictability of it. I was meeting beekeepers sometimes that I didn’t know, that somebody would refer me to a beekeeper that was, do some filming. They’d say, “Okay, you’re going to meet this guy at this Google pin here.” I was like, “Okay.”

I don’t know who I’m meeting, it’s the middle of the night. It’s off in the middle of nowhere in the Central Valley, and then I’m going to call and say, “Okay, it’s not going to be two trucks here. It’s going to be four trucks, and it’s going to be 60 miles away.” I would just run off and do it. I just had to be really flexible with how I approached it. It was tremendously rewarding. It was just a great adventure for me.

Kim: I believe that. Jeff you ever been able to get up and watch the almonds?

Jeff: No. Hey, maybe we should take the podcast out to the almond orchards one of these springs.

Kim: We’ll give that a try. This year I’m glad I’m not in Northern California however.

Jeff: May be a little muddy, I think.

Kim: It’s wet out there this year. Peter, you do documentary films primarily as I understand it, and I watch them. I go to theaters and wherever to watch them. How does the mechanics of documentary are they different than a Hollywood movie? Or how do they get distributed? Can you share a little bit of that because I really don’t understand any of that?

Peter: There’s no one way it happens. That’s the short story. I mean, this film was done, I originally went out to do this, and I was going to sleep in my car in order to capture the almonds because I knew I needed to get something and I wanted to get the almond pollination. Use that as a little bit of a put together a little trailer, if you will, to raise some money.

Luckily, I was able to raise a little bit money before I got out there, so I was able to get a hotel room, every once in a while, and [laughs] well needed shower. Most of the work in this film was done, it wasn’t done for anybody. It wasn’t done for a broadcast or anything, it was all done on my own, if you will, my wife is a producer and she wasn’t out in the field with me but she was keeping me out of trouble. She’s a very experienced documentary producer.

I basically-- it was a lot of sweat equity. I just kept on working to try and capture the different elements that I had in mind, which was to follow a season of pollination with a bunch of different beekeepers, and use that journey as a way to try and tell the story of pollinator decline and the dependence upon bees for agriculture in their food system. I just kept on working.

I’m a cameraman and so I own my own gear. If I got a call from somebody, and this happened and say, “We’re going to move our bees out tomorrow, and it’s going to be in Maine.” If I could, I could hop in the car and head off to Maine and start shooting that night or Massachusetts or Pennsylvania. I did a lot of running around very last minute because you’re dealing with the bees and agriculture and nature, none of which are predictable.

All that came together into a documentary film we edited for over a year. Shaving and shaping the story down from about 200 hours of footage to about an hour and a half, and to try and tell this, it’s a very complex story in that 90 minutes. We worked really hard to try and tell an interesting, coherent and diverse story with all the footage that we had.

Now, we’re at the place where we’re trying to find a home, find a distribution home for it. We’ve been in one festival so far, and we have a couple more scheduled in Sonoma and also Newport Beach. Then we’re waiting to find out about a whole bunch of other festivals throughout the year. The hope is that, that we’re going to find a home for the film on a broadcast or streaming, and I don’t know, whether that’s going to be a Netflix or an Amazon or Hulu or PBS. All of them are potential places that this could find a home.

Kim: When you get a schedule on these people, certainly keep us in mind so we can get beekeepers out to see it, they can’t see it if they don’t know where it’s going to be. The more you share with us, the more we’ll share with them. I’m excited to get that information out there.

Peter: Thanks. We have a website, the pollinators.net on there will be information about where the film will be playing and festivals. Ultimately, what sort of distribution we’ll end up with the film. The great thing about it is that beekeepers are a very active group of people. It’s a network that virtually in every state, almost every county in the country, there’s a beekeeping organization, a beekeeping club, if you will.

Part of my plan is when I go to a different place to reach out to those people, and that happened in Missoula at the Big Sky Documentary Film Festival, and we were there. It’s part of my initial to try and get interested in the film and get the word out. Beyond just the distribution of the film, what I want to do is really put the film out for extensive outreach, ultimately, and that might be going to the different beekeeping conventions, go to universities, go to schools, with people are already interested in doing that.

This is a tool that I think they really want to use ultimately to make people aware of where their food comes from, and the importance of bees in that process. Our culture is two or three generations away from the farm, people have lost a little bit of a touch about, where their food comes from? If people can go into a supermarket and pick up an apple and think for a second about the fact that was pollinated by an insect, whether it’s a honeybee, or a bumblebee or some other type of bee. That would be a great goal for me.

Kim: Certainly, good observation about two generations away from being on a farm, it’s about right, which is just long enough to forget most of what we knew. Speaking of farms, you worked with some farmers on there that are really doing the right thing. I was glad to see it actually being done. There’s a couple of guys that you were talking to there.

Peter: Yes, Lucas Criswell and his father William, down in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. He’s a young guy. In a lot of ways his dad and he worked together. They’re very funny, amusing couple of guys, and they play off each other and they have a great time. Lucas is really an interesting guy. He’s very much a leader in this field. He’s trying different techniques to make it better for growing better for the bees, better for the environment, better for the soil.

Ultimately, it does come down to the soil. It’s interesting that a lot of farmers I found they’re looking from a cost perspective to which is very interesting that they’re interested in all of those things about the safety and health and environment. It’s also about the bottom line, and Lucas had a great line that he said, “I like to write my name in the back of the check and not the front of the check.”

[laughter]

Kim: Good observation. Peter, one of the other things that I saw that was scary, getting away from farming, but not too far away was what they’re finding in beeswax. Jew and Marianne Fraser, were talking about that, certainly, they’ve been leading the charge on finding it but it’s scary.

Peter: The bees, they bring things home with them and the wax is a repository for a lot of these pesticides, fungicides and herbicides. They bring it home unintentionally a lot of it and it gets stored in the wax and the wax is a repository for it, which is a little alarming. The bees don’t have a lot of choice about that. I think they have a way of sequestering stuff when they know it’s there, they seal it, but it’s not like they really clean house. [laughs]

Kim: They can’t. The wax just soaks the stuff up like a sponge. We just did a program with Reed Johnson from here in Ohio State, where they were spraying a pesticide on the bees when they were during blossom. That’s about as bad as it gets. The subtle way that the Fraser’s were talking about is the bees visit the flowers, they bring it back home, it goes into the wax, and then their babies are brought up surrounded by this stuff. I don’t know how do you stop that?

Peter: I think part of the answer is using less pesticides, less herbicides, less fungicides. I think that one of the things that we’re doing and we collectively as we’re using things that instead of using integrated pest management system we’re tend to use pesticides that are coded on seeds, and again, it’s another great expression Lucas had. It’s like taking an aspirin in the morning because you might have a headache.

Instead of seeing the problem that’s there and treating for it, you’re treating for a problem that you don’t know exists yet. I think that might not be the best approach for it. I think an overall using less pesticides, herbicides and fungicides would be a great first step. What’s important here also is the fact that consumers, it’s not just farmers that are doing this, but consumers you go into any hardware store and you’re going to find shelves and shelves of all of these products.

I think that many consumers are quick to use them without thinking about the impact that they will have and whether that’s a real problem or not. Anything in nature, once you start pulling things out, it becomes unstable system, and you’re killing beneficial insects as well as pests and you might be creating more of a problem by doing that.

Jeff: One of the things that was brought up in the movie that I did was unaware of was the use of seven to thin the blooms and the apple blossoms. I’ve never heard that before. Wow.

Kim: It’s tough on bees or it can be.

Peter: Yes.

Jeff: Or anything, any insect.

[laughter]

Peter: It was very interesting to discover that, and of course, not apple, all apple growers do that, or all fruit growers do that. I guess there’s something about the acidity of the seven that will kill the bloom on some trees. That’s why they want to thin the blooms out so they don’t have too many apples on the trees so they cut their production, have bigger apples, the ones that do survive. Again, is it the best thing to use? First of all, that’s a question that I would ask, and I don’t have the answer to that.

Then it’s also about communication. These growers, bees have wings and they fly as Dave Hackenberg says. If one apple orchard is using seven and does not know that their neighbor might have bees still in there, then you can have a real problem. I think that communication could be a real-- there could be a lot better communication amongst farmers, neighboring farmers about, call up your neighbor, text your neighbor. The technology is there. You say, “Hey, I have to spray to thin my bees, my apples, are your bees out yet.” Just that little bit of communication might save a lot of bees and make for better relations amongst farmers and beekeepers.

Jeff: Definitely. That was amazing. That was one of the surprising things I heard in the movie.

Kim: We did a story not long ago on pollinating apple trees with drones and that’s what they’re after. They load up the drone with pollen and they hover it over a tree and they blast pollen down, they fertilize the king blossom and move on.

They can do it at night, but it’s the king blossom that they’re looking for, and that’s where the money is. I’m envious. You had a chance to talk with Bill McKibben. I read his stuff. I think I’ve read everything that he has written. We’ve reviewed several of his books in our magazine. That was a very pleasant surprise when I saw that.

Peter: He’s a great guy. He narrated my short film and I’ve had the great fortune to work with him a few times in different films over the years, and he was very willing to do it. Here’s an environmental background as you say, he’s a real leader in the environmental movement. He came in and I wanted to, because he has a great perspective on the overall system, which I really wanted somebody to be able to put forth.

He has a very direct way of laying it out for, he’s not a beekeeper. He has friends who are beekeepers, but he’s not and he’s not a farmer, but he understands how the whole system works. I think sometimes it is very helpful to have somebody come in and give you a broad perspective from 10,000 feet up as how the whole system works together and to elucidate what happens when you start picking it apart and simplifying it.

Kim: That’s 10,000 feet view, that’s what he has. His work with-- is 350 his group?

Peter: Yes, 350.org.

Kim: Is in it gibing carbon dioxide-- Then Sam Ramsey, we did a program with him a while back and what he thinks is important is really important. His findings have been-- it’s changed how we think about varroa, certainly.

Peter: He’s amazing. I tried to get him for about a year and he was just too busy. He was finishing up his doctorate at the time that I was doing the movie, and just luckily got him right at the end. He was just a dynamic, enthusiastic guy whose work as you say, has really changed the whole approach of varroa to treating varroa.

I think he’s a great example of having innovative thinking that can look at it in a different way and approach it from not accept-- his groundbreaking work is based on going back and looking at other people’s work that was basically misinterpreted. By doing that, basically threw out all the work that was there and started new and gave everybody a new perspective on that. I was thrilled that he wanted to be part of it. I wish I could have spent more time with him, but he’s a very busy guy.

Kim: We were lucky, Jeff, to get him to sit still for an hour back then, but the parallel that you just brought up Peter is interesting. Sam went back and looked at old stuff and interpreted it a different way, and those farmers in Pennsylvania went back and looked at old stuff and interpreted it a different way and bringing it back. The parallel between these two industries is interesting.

Peter: I think it’s true. Some of the techniques these farmers are doing, as I mentioned before, are not exactly new techniques. Cover cropping and crop rotation are old techniques, our grandparents are doing that, our great grandparents are doing that, but we’ve gotten away from it. I think that a lot of agriculture has gone into more of a chemically dependent system instead of using plants and rotation and allowing that to work for us.

Where we are right now, in my opinion, again as a nonfarmer is that there are a lot of innovations in terms of technology that are very advantageous to farming that you can do a lot more efficiently now. I think that the combination of some of these old techniques with the new technology, whether it’s computer-based organizational system or equipment is a good time. I think it’s an opportunity particularly for young farmers that are starting out now that can try and make small changes and make a big difference.

Kim: Certainly, hope some of them do. It’s not working the way it is right now. Did you enjoy talking to Susan Kegley? She’s always been an interesting, I use the word character and I don’t mean it. She’s an interesting lady.

Peter: She was awesome. I just adored her from the get-go, and she spoke so clearly and to the point. I think that she made so many good points in the film, and her enthusiasm for bees and insects is just palpable and infectious, so to speak. She also brought up a very interesting point that I included in the film, that a lot of the changes in agriculture, she believes,, are going to come from the ground up. They're the choices that we as consumers make, that if we want to make a change in how things are grown it's our choices in the supermarket that will help drive those choices. That's a capitalistic view that appeals to so many people across the spectrum. I just really enjoyed that. She was just so much fun to be with. I learned so much from her.

Kim: The point you just said, if there's demand, you're going to have people but without the demand, hopefully what she had to say, what all of these people are saying is we'll change the demand so that farmers start looking at things a little bit differently.

Peter: It's one of the big goals that I had in terms of making this film, was that a lot of people know that there are problems with bees, and a lot of people realize that there's a pollinator decline. That's a scary issue for a lot of people. I think it would be really easy to make a film that was just very bleak and said all the bees are dying and we're in trouble. What I really wanted to do from the get go was to try and incorporate people that are making a difference and people that are working towards a difference and offer hope and opportunities for anybody who watches this film, that there's something as an issue that makes this so interesting to me, there's something about this issue that everybody can do something about.

I wanted to make it very actionable. That could be really, really simple things like buying honey from a local beekeeper. They're just around everywhere. Choices in the supermarket, what you plant in your garden. If you're more adventurous, you could get involved in politics and try to change policy. I think there's a whole spectrum of actionable things that people can do to make a difference in this because it has to come from us and it has to come from the people. I think that was one of the most appealing things about working on this project for me, was I wanted to try and make people aware of this problem, what some of the causes are, and then also give them some hopeful choices that they could make in their own life that they could go out and make a difference.

Jeff: It was fun to have, I can't remember who said it, it might have been Susan who said this. It's the green lawns, it's a problem. If you want a green front lawn, that's fine, but let your backyard be wild. Let the dandelions come up in the back and it's not either. It's not black and white. You can say, well, you can find a way to make it work within where you are. I thought that was a great message.

Peter: That was Maryanne Frazier that said that. She's exactly right. There's something, even if you live in a city in New York City or Boston or Durham or wherever, having these little pockets of nectar and pollen through plants, whether they're vegetable plants or whether they're flowering plants, create an opportunity for pollinators to survive.

If there's nothing for them to live on, they can't survive. I think that all those little choices can make a big difference. Doing what we do on a lawn. Having clover in your lawn is like such a simple thing, and it makes a big difference.

Kim: I do a fair number of interviews with newspapers and things, and one of the things, the questions the reporter almost always leaves is, "What can I do?" My simple answer is, "Plant a flower, feed a bee." Zach Browning, of course, plants a lot of flowers in his bee and butterfly work. It's good to see some solutions getting bigger and better, I think.

Peter: I think the CRP, the Conservation Reserve Program, really a lot of that has been, I think, converted to corn and soy. A lot of that land that traditionally was left vacant for wildflowers and natural growth has been converted. Zach and the Bee and Butterfly Habitat Fund have really worked very hard at establishing these these mixes and these opportunities for forage in particularly in the Midwest and the North Dakota and South Dakota. It's just great. They're really doing inspiring work and working with the USGs with those projects about figuring out what the bees are eating, when they're eating it and how it's affecting them nutritionally. Again, it's a use of technology that you can really dial in and create a very healthy environment for bees.

I think that's something that's also an important thing is nutrition, which comes along just like us, if we all eat Twinkies you're not going to be healthy but if eat a wide variety of different things is a healthy way for us to live. It's the same way for bees. They need a diverse and healthy diet of of pollen and nectar sources.

Kim: I know Brett is associated with the pollinator stewardship, and that's one of the things that they're aimed at doing is getting bee food where there was grass, getting bee food on roadsides and those sorts of things. There's a lot of solutions that are trending, is that the right word? I don't think we're there yet but you can see them from here and if we can keep them going, I hope that this film gets more of this going because now people can actually listen to the people who are making it happen and see that it's working. Your actions here I think are a good hive tool for moving things along.

Peter: Thank you. The wild flowers is an interesting thing. I see it around here where I live in New York, that every once in a while I'll see a truck going down a highway that's spraying in herbicide on the side of the road, and people don't think twice about that but as a beekeeper I look at that and I say, "There goes a lot of habitat. There goes a lot of forage for bees." Even if it's not my bees, it's somebody else's bees or other pollinators. I think that those choices, while they're convenient and maybe easy, may not be the best choices. Leaving some of those wild habitat and forage is a really good opportunity. Just letting those be is a really important thing for bees and other pollinators.

Kim: How well did you eat when you were talking to Dan Barber?

Peter: When we did that interview where we set up at Stone Barns was right next to the bakery. I have to tell you, we ate pretty well. That place, Stone Barns Center for Agriculture, is amazing. It's a place that I've been to, and it's a place that I've actually taken classes at. It took a class on soil there probably close to 10 years ago just because I have an interest in gardening. Dan is also one of those big thinkers who was able to connect the dots literally between the plate and the field. It was a real honor to be able to sit and talk with them about those things.

The farm itself, the Agriculture Center, Jack Algier and his whole team is really very inspiring because they're really walking the walk about how to make these make these changes and work with the system in a very productive way. What they're getting out of it is very good food for the restaurant, but also a big part of their mission is to teach other people about those choices. One quick story, an experience I had there a couple years ago. My wife and I went down there to visit during the day and they have a little cafe there and they have a demonstration garden.

I was in there, I was looking at the flowers, and of course, I was watching the bees and what was going around. I heard a woman behind me say, "Is this corn or is this wheat?" I turned around and I thought she was joking. I turned around. She was standing there pointing at the most iconic ear of corn on a plant that I had ever seen. I thought she was joking. I almost laughed. Then I thought that's pretty incredible that A, she was comfortable to ask that question, and B, that she was in a place where somebody could answer that question respectfully and make it a teachable moment.

I thought that pretty much embodies what that place is all about. You shouldn't assume that everybody understands how agriculture works, but it's so important to have a place where people can go learn how food is grown, the importance of good soil and where their food comes from.

Kim: It looked like you were having fun when you were there. I didn't even take away that much when you were there, so thanks for the details. I may have to drive out there.

Peter: It's worth a trip. I've been lucky enough to eat in the restaurant, and it's unlike any other place most people would ever eat. Dan Barber is in the top 10 chefs in the world and really innovative at ways of looking at food in our food system.

Jeff: Well, Yes, that was really interesting, that's for sure. At the end of it all, and you're looking back at the film and the finished product, was there anything you discovered, anything you learned that make you reconsider how you're keeping your own bees at home? Anything you changed as a beekeeper?

Peter: Interesting.

Kim: Did you use a forklift? [laughs]

Peter: My beekeeping keeping methods are pretty traditional. I work off of Langstrop hives, and I just have just a few hives. I like wax foundation. I like the smell of it. For me, it's a very tactile sensory experience. I guess one of the things that I had really come through was what I do maybe affects my neighbor. That's in this time of varroa, the spread of varroa, that's an important thing. It's almost like it reminds me a little bit of the vaccination debate. That my bees, if they have varroa and they're a weak colony, then I could be really hurting somebody else's bees by doing that.

That's one thing that I thought, was that I'm a little bit more on top of. I had a couple of years when I did more of a homeopathic method of varroa treatment because I didn't want to deal with a lot of chemicals, but I found somewhere in between. I personally have started to use hopgard, and I think that's pretty good. That's been working for me where I am. I think that the great thing about beekeeping for me is that it really makes me slow down and pay close attention to what's going on in the world around me, to wherever I am, to look at what's in bloom, what people are eating, what flowers the bees are on.

I like that connection to nature that beekeeping gives me. I never get tired of just having some time out in a beehive and just enjoying it because I always see something different and I always learn something.

Jeff: I think any beekeeper would agree with you on that statement.

Kim: One quick story, Jeff. I was at a meeting this weekend and I was on a panel, a Q&A panel, and one of the people in the audience said, "We know you get around a lot." He says, "What's the one thing that you've noticed that almost every beekeeper, all beekeepers, have in common?" I think what you just said was a lot of it, is beekeepers like getting together, A because they're always going to learn something from another beekeeper, but B, they're with a whole bunch of people that don't think they're crazy. [laughs] You put your hands in a box of live, stinging venomous insects, and a lot of people are going to take a couple of steps back.

When you're with other beekeepers, you don't have to be that defensive and you have that ability and time and opportunity to notice those kinds of things.

Peter: It's true. One of the things that I really wanted to show is just a lot of people have a fear of bees as a stinging, venomous insect. More often than not, it's probably caused by an incident with yellow jackets when they were a kid. I think that it's important for people to understand that bees don't want to sting you because they die in the process and they only do it when they're threatened and feel like they're in danger. I really wanted to show people the charismatic aspect of bees and how wonderful they are. I think that one of the people that I included in the film that exemplifies that is Lee Catherine Bonner down in Durham, North Carolina.

Young, inspiring woman who runs a company called Bee Downtown. She was great. She was out there in just shorts and a T-shirt, and I thought, "I would never do that." She was out there and she wasn't getting stung, and she just approaches it in a very gentle, caring way. I think her whole approach, literally and figuratively, is that we need to really pay attention to these important pollinators around us.

Jeff: That's really good. Well, Peter, we really appreciate you taking the time this afternoon to join us onBeekeeping Today podcast. It's really been a pleasure having you on the show. Also, it's been great watching the movie, and I look forward to seeing it get out and about in the public in the coming months.

Peter: Well, thanks very much for having me. I really appreciate it. If I can plug the website a little bit, thepollinators.net. Thepollinators.net is where information will be about the film as it comes forward. I'll be sure to keep you all in touch because what you guys are doing is a great thing and spreading the word and educating people about bees. I think that's all of our goal.

Jeff: Definitely. Thanks for that. I'll make sure that all the websites that you've mentioned and we've mentioned on today's show are in the show notes so that listeners can go out and research as they wish.

Peter: There was one other thing I wanted to say about just the beekeepers themselves. One thing that I took away from working with people like David Hackenberg, Davy Hackenberg, Brett Adie, Glenn Card, Zach Brown, incredible group of people that are so dedicated to their bees and really care about them. I think that some people might think that they move these bees around with pallets and forklifts and tractor-trailer loads around the country, but these beekeepers really, really care about their bees. When you have a bee kill, like I had the misfortune of being able to film that a couple of times. It made me sick to my stomach and it really hurt them.

I could tell how much their bees really mean to them. They're not pets, but they do care about them. I think that's something that I really took away, how hard these guys work and to do agriculture and pollination and how much they care about what they do.

Jeff: The movie is really well done and that respect you have for the beekeepers really comes through in the movie. It's fun to watch. Really good. Well, we'll play out on one last clip from the movie The Pollinators that is produced and directed by Peter Nelson, our guest today on the podcast. This clip is of Mary Anne Fraser talking about what we can do as beekeepers and as neighbors and how we can take care of each other and all of the pollinators on the planet with our choices that we make every time we go to the store. Thanks a lot, Peter. Thanks a lot.

Kim: Yes, Jeff. Peter, thank you. Like I said, it's good to meet you finally, but I thoroughly enjoyed the film.

[music]

Peter: Well, thanks so much for having me. I really appreciate the opportunity to share this film and I look forward to sharing with as many people as I can.

Kim: We'll see what we can do to help.

Peter: Thank you.

Jeff: Thank you.

The Pollinators - Maryann Frazier: We ourselves have become users, consumers of pesticides. You can see that very easily when you go to Walmart, you go to Lowe's, you go to Home Depot, and the shelves are lined with pesticides and particularly herbicides. You think, well, herbicides aren't toxic, but herbicides are completely, in many places, eliminating the forage that bees require. Bees require flowers, they require nectar and pollen-producing flowers. This widespread use of herbicide, not only in agriculture but also by homeowners, everybody wants a magnificent green lawn without a single dandelion or clover plant in that lawn or a blooming flower in that lawn.

That's a food desert for bees. If you want a green lawn, great. Let your front yard be green and allow the backyard to have some dandelions and clover and grow a pollinator garden. Herbicides, fungicides, and insecticides, all three of those categories are problematic for our bees. Again, it's not just honeybees, it's all of our bee species.

Jeff: Well, that was a great discussion with Peter about his movie, The Pollinators. I really enjoyed that movie and I really enjoyed the discussion.

Kim: I think, Jeff, that last little bit there you just had with Maryann Frazier, you couldn't get better advice. Grow, feed a bee, plant a flower, and let's see if we can keep away from the pesticides. I got to tell you, I think our industry is really fortunate to have somebody like Peter make a film like this because he's also a beekeeper and has been one for, what did he say, 28 years? Something like that. He has the insight of knowing what's important already, and he has the experience to be able to show what he thinks is important and what beekeepers think is important and to be able to show what people who aren't beekeepers need to be able to see and to know when they watch this film.

I think in the same amount of time, somebody with different or less experience would not have been as successful. As I said, I think we're just darn lucky to have a beekeeper be a movie maker.

[music]

Jeff: Well, that about wraps it up for this episode. Before we go, I want to encourage our listeners to rate us five stars on Apple Podcasts or Wherever you download and stream the show. Your vote helps other beekeepers find us quicker. Even better, write a review and let other beekeepers looking for a new podcast know what you like. You can get there directly from our website by clicking on reviews along the top of any webpage. As always, we thank Bee Culture, the magazine for American Beekeeping for their continued support of Beekeeping Today podcast. We want to thank our regular episode sponsor Global Patties. Check them out@globalpatties.com.

Thanks to Strong Microbials for their support of this podcast. Check out their probiotic line at strongmicrobials.com. We want to thank Better Bee for their longtime support. Check out all their great beekeeping supplies at betterbee.com. Thanks to Northern Bee Books for their support of Bee Books Old New with Kim Flottum. Check out all of their books at northernbeebooks.co.uk. Finally, and most importantly, we want to thank you the Beekeeping Today podcast listener for joining us on the show. Feel free to leave us comments and questions at leave a comment section under each episode on the website. We'd love to hear from you. Thanks a lot everybody.

[01:01:12] [END OF AUDIO]

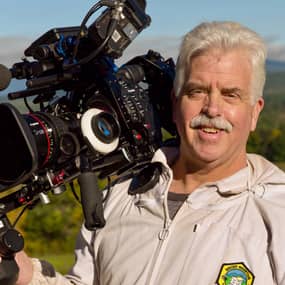

Film Maker, Director

Peter Nelson has photographed a wide variety of feature films, commercials and documentaries in a multitude of film and video formats. His signature naturalistic style has taken him around the world to capture life as it happens for fiction and non-fiction films alike. Feature credits include Emmy award winning ART & COPY, SICKO, A TALE OF TWO PIZZAS, PIPE DREAM, SUITS and the cult New York romantic comedy ED'S NEXT MOVE which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival.

He has done domestic and international documentary work for PBS, HBO, BBC and Granada Television. Recent commercial work includes campaigns for Google, BlackRock, Dunkin Donuts, Dell, SBLI, ESPN/NASCAR and Perdue. Other commercial credits include spots for PBS, Stop and Shop, Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, Lifetime, Coca-Cola, Champion and Calvin Klein. Peter received a BFA in Film and Television from NYU's Tisch School of the Arts.